MP Twitter Networks

Originally published in 2021 on my old website, now reuploaded here including nicer looking charts.

Introduction

In recent years, Twitter has become increasingly prominent in politics, not least due to ex-US President Donald Trump’s questionable use of the platform. But across the pond in the UK, politicians’ Twitter presences have been gradually growing over the years, as more MPs (and their teams) get online and start tweeting. Nowadays, with the majority of UK MPs on Twitter, there is an opportunity to gain insight into a number of areas, including MPs’ networks, political beliefs and public appeal. This insight can be gleamed from analysing MPs’ behaviour on the social network; from what they tweet, who they retweet, who they follow, who follows them etc…

The area I would like to focus on here is the parliamentary twitter network as there is not a particularly large amount of research around this. A few previous reports and articles have shown than UK MPs generally tend to cluster together within their own parties, with regard to following relationships and also re-tweet networks (McLoughlin et al., 2019), (Sleeman, 2015), (Weaver et al., 2018). Although, events like the EU referendum have lead to more cross-party interaction in terms of at least tweeting behaviour (Weaver et al., 2018). However, most of this research is a number of years old and doesn’t really reflect the current parliament since the 2019 election. Moreover, the follower-following relationships of smaller parties (e.g. Lib Dems, SDLP, DUP) have not been looked at individually, as well as the within-party follower-following networks. So, in this post I am going to look at the follower-following relationships between UK MPs, with a focus on smaller parties’ overall networks and also on the within-party networks of the Labour and Conservative parties.

Data

The data was gathered in February 2021 from Twitter’s API, using the Tweepy package in Python (as the data is from February, it doesn’t take into account any changes since then, e.g. Neale Hanvey & Kenny MacAskill defecting from the SNP to the Alba party). I downloaded a spreadsheet from https://www.politics-social.com/ which contained each MP’s Twitter name, their party and their constituency. I then queried the API using Python to return a list of who each MP followed, along with their bio, follower count, like count, status count and a few other metrics. I ran into a few issues, e.g. some MPs had deleted their twitter accounts or had private profiles so I could not view their following list - so I removed those MPs from the dataset. As Twitter’s free API has limits on how much data you can download in a given period, it took over 10 hours for all the data to be collected. I then did a bit of data manipulation in Python and R to get the data into the correct format for analysis and visualisation. Python and R code available here.

Outline of MP Follower-Following Relationships

In Table 1, I have arranged a number of summary statistics for each party. I have used median and Interquartile range (IQR) stats as there are a lot of outliers and the data is not normally distributed - you can see the distribution of the number of MP Followers for all parliamentarians in Figure 1. As previous research has shown, generally MPs’ following-followers relationships tend to mostly be to their own parties. This leads to the average MP followers statistic mostly reflecting the number of MPs on twitter for each p arty, although this relationship doesn’t really hold for some of the very small parties (see the below table).

Table 1: Summary of parties’ twitter followings

However, while the Conservatives have on average more MP followers (i.e. followers who are MPs), they actually have less median total followers than most other parties, including Labour and the SNP. The Green Party has the 4th highest average MP followers and by far the most average total followers, but that is obviously due to there being only one (popular) Green MP - Caroline Lucas. The SNP has a modest median total followers relative to the Tories, Labour and the Lib Dems, possibly reflecting the geographic focus of the party. The Lib Dems have quite a high median total followers and low median MP followers. The other minor parties have fairly similar total followers and MP follower counts, apart from Sinn Féin, who have a relatively low average MP followers and high median total followers, and the SDLP, who have very high values for both stats. Additionally, the Tories and Labour have quite a high variability of total followers, as measured by IQR, compared to other parties.

Figure 1: Distribution of MP followers by party

Figure 1: Distribution of MP followers by party

Furthermore, ranking MPs by their number of MP followers can show some interesting results (see Table 2 below). Firstly, the majority of the MPs most followed by other MPs are Tories, with senior leadership and ex-leadership figures taking the top spots of the ranking. The Speaker, Lindsay Hoyle, however, comes in 3rd, reflecting his apolitical role in parliament. The only other non-Tory MPs in the top 20 are two Labour MPs - Keir Starmer and Ed Miliband.

Table 2: MPs followed by the most other MPs

One relationship, which I mentioned earlier and would like to expand on, is that while the Tories do on average have more MP followers than their Labour counterparts, Labour MPs on average have more total followers. This is visualised in Figure 2 (below) - note the log scale on the y axis. This seems to show that although the Conservatives are more linked to one another in terms of following relationships, they actually have a harder time getting follows from the general public compared to Labour. I suspect this is due to Twitter having a relatively left-wing user-base, combined with Labour MPs possibly having a stronger online presence. The distribution of MPs from other parties is also visible in the figure, with most of them clustered in the left hand side of the charts.

Figure 2: Relationship between total followers and MP followers

Figure 2: Relationship between total followers and MP followers

A great way to visualise the following-follower relations between MPs is network visualisation. To do this I used a piece of open source software called Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009). In short, networks are made up of nodes and edges (connections) between the nodes. I used an algorithm to create the network visualisations called ForceAtlas2 (Jacomy et al., 2014), which essentially creates a graph where each node is clustered together with other similar nodes (in terms of their connections). In this case, each node represents one MP and each edge shows that one MP follows another MP. The nodes are also coloured based on party affiliation and sized relative to the number of connections each MP has to other MPs (the labels are also thus sized by the same metric). Both follower and following relations are included.

From running this algorithm, the below visualisation (Figure 3) was produced. As we can see, each of the large parties have their own clusters, but there are some MPs from both the Conservative and Labour who have floated off a bit into the centre of the graph, as they have quite a few connections to MPs from other parties relative to their own parties. Notably, Eleanor Laign, Nadhim Zahawi, Matt Warman, Andrew Rosindell and James Cleverly for the Tories and Darren Jones, Wes Streeting, Luke Pollard, Chris Bryant and Keir Starmer for Labour. The Speaker, Lindsay Hoyle is by no surprise right in the middle of the graph. Generally the minor parties (including the SNP) are quite clustered together, apart from the DUP, but I will elaborate on this further in the next section.

Figure 3: UK MP Twitter network

Figure 3: UK MP Twitter network

While Figure 3 does visually show how parties are interconnected, I also thought it would be nice to quantify how insular parties and MPs are (e.g. what percentage of MPs followed by each specific MP belong to the same party as that specific MP?). You can see in Table 3, that Conservative Party MPs were the most insular on average, followed by Labour and then the SNP and other minor parties. There were also 38 Conservative MPs who only followed other Tories, while there were only 5 Labour MPs who purely followed other Labour MPs. There were no MPs from other parties who only followed MPs from their own party. Additionally, in Figure 4 you can see that while Tory MPs in total had nearly twice the number of following relations to their own party compared to Labour’s own party relations, the Tories had fewer following relations to every other party (except the DUP) than Labour. One possible way to explain the difference in insularity across parties is that it is related to party size; less dominant and smaller parties require more collaboration with other parties to make an impact. The Conservative party, which has been the largest party and continuously in government since 2010, relies less on cross-party relationships compared to the other parties, so is therefore the most insular. You could also consider this from the opposite angle, looking at who each specific MP was followed by or you could look at mutual following-follower relationships.

Table 3: Parties by insularity of following relations

How Do the Minor Parties Fit Into the Network?

Although it is fairly easy to see how the Labour and Conservative parties interact with one another, smaller party MPs’ connections are quite hard to distinguish in Figure 3. In Figure 4, you can see the number of following relationships from each specific party to each other party (read the graph from the top left across and down to find the number of following relationships from the source party (top left) to each target party (bottom left) and vice-versa for the number of followed relationships).

Figure 4: Number of following relationships between parties

Figure 4: Number of following relationships between parties

Overall there are some interesting observations that generally correspond to each party’s political stance and to the extent they have worked with each of the other parties.

The Alliance Party has a fairly even number of links with the Tories and Labour, and a number of links to the Lib Dems and the SNP and some of the other minor parties and NI parties.

The DUP mostly has links with the Conservative party, likely because they have similar ideologies and also have worked with the Conservatives previously to prop up Theresa May’s government. They have few links to Labour and the SNP, but a number of links to some of the other NI parties.

The Green Party, although having only one MP, have quite a number of links - especially to the Labour party. They also have a number of connections to the SNP, the Lib Dems and other minor parties like the SDLP, but few links to the Tories, relative to the number of connections to other parties and the size of the Tory party.

The Liberal Democrats live up to their reputation as the party of the middle ground (at least excluding Brexit), as they are well connected to the two main parties and the SNP. They also have some links to parties like the Greens, SDLP and Alliance.

Plaid Cymru are characterised by having denser links to the SNP compared to any other minor party and a roughly similar number of linkages to both the Conservatives and Labour.

The SDLP have more connections to Labour than the Conservatives and quite a few links to the SNP (more than Alliance, DUP and Sinn Féin, but less than Plaid Cymru and the Lib Dems).

Sinn Féin have relatively minimal links to any of the other parties (relative to the number of MPs they have), especially compared to other NI parties like the DUP, Alliance or the SDLP, which is possibly representative of their abstentionist approach to the UK parliament. Although they do have more links to Labour than the Tories.

The SNP, being the 3rd largest party in Westminster, have lots of connections to both Labour and the Tories (more to the former) as well as to most of the minor parties. To better see the SNP’s links to other smaller parties, take a look at Figure 4.

Within-Party Communities

It is also possible to look at the follower-following relations between MPs of just one party. The networks of Labour and the Conservatives are of course the largest and in my opinion thus the most interesting to consider when looking at within-party relations.

For these networks I have filtered the edges so that there are only connections between nodes if MPs have a mutual following relationship (i.e. they both follow each other’s accounts). I didn’t do this in the previous graphs as I thought it might remove a lot of detail for parties with few MPs and MPs with few connections, but looking within larger parties, I want to slim down the number of edges and focus on the stronger mutual following relations between MPs.

The networks are again made using the ForceAtlas2 algorithm, so nodes are situated near other similar nodes in terms their position in the network. I have also divided the network into a number of groups based on a community detection algorithm call the Louvain Method (De Meo et al., 2011). This algorithm divides the network into groups of “modularity classes” that generally have denser connections to nodes within the same class that to nodes within other classes. The algorithm has a parameter called “resolution”. Increasing the value of the resolution divides the network into fewer and larger groups and decreasing the value creates more and smaller groups. There thus seems to be a bit of discretion involved in choosing the resolution. I found that dividing the network into many small groups did not really produce anything that interesting and was quite noisy. Having 2-3 main groups per network seemed to be more revealing in terms of mutual following relationships.

Looking firstly at Labour and employing the Louvain Method, I uncovered three communities within the network - designated by the different colours in Figure 5 (red, yellow and cyan). I’ve also created an interactive version of Figure 5 - https://scottw2.github.io/UKMPsTwitter/LabourNetwork/. For some reason the interactive graphs are upside down compared to the static ones.

The red community is generally those MPs to the political left of the party, e.g. Jeremy Corbyn, John McDonnell, Zara Sultana, Clive Lewis, Rebecca Long-Bailey. As another example, 33 of the 34 MPs in Labour’s Socialist Campaign Group, a left wing pressure group of MPs, can be found within the red community, with the remaining one in the yellow group.

The cyan community appears to be characterised by generally being comprised of Labour’s more centrist or soft-left MPs, e.g. Ed Milliband, Keir Starmer, Jess Phillips, Hilary Benn and Margaret Hodge. So it looks like the red and cyan communities can broadly by divided by left-right politics.

Those within the yellow community are probably MPs that are generally somewhere in the middle of Labour’s political spectrum, as demonstrated by most of the yellow community being in the centre of the network. This community can broadly be categorised by having a more evenly distributed number of links to red and blue community members compared to the balance of links the MPs in those two communities have with MPs in their own community compared to colleagues in the other community.

Figure 5: Labour network of mutual followers - coloured by modularity class

Figure 5: Labour network of mutual followers - coloured by modularity class

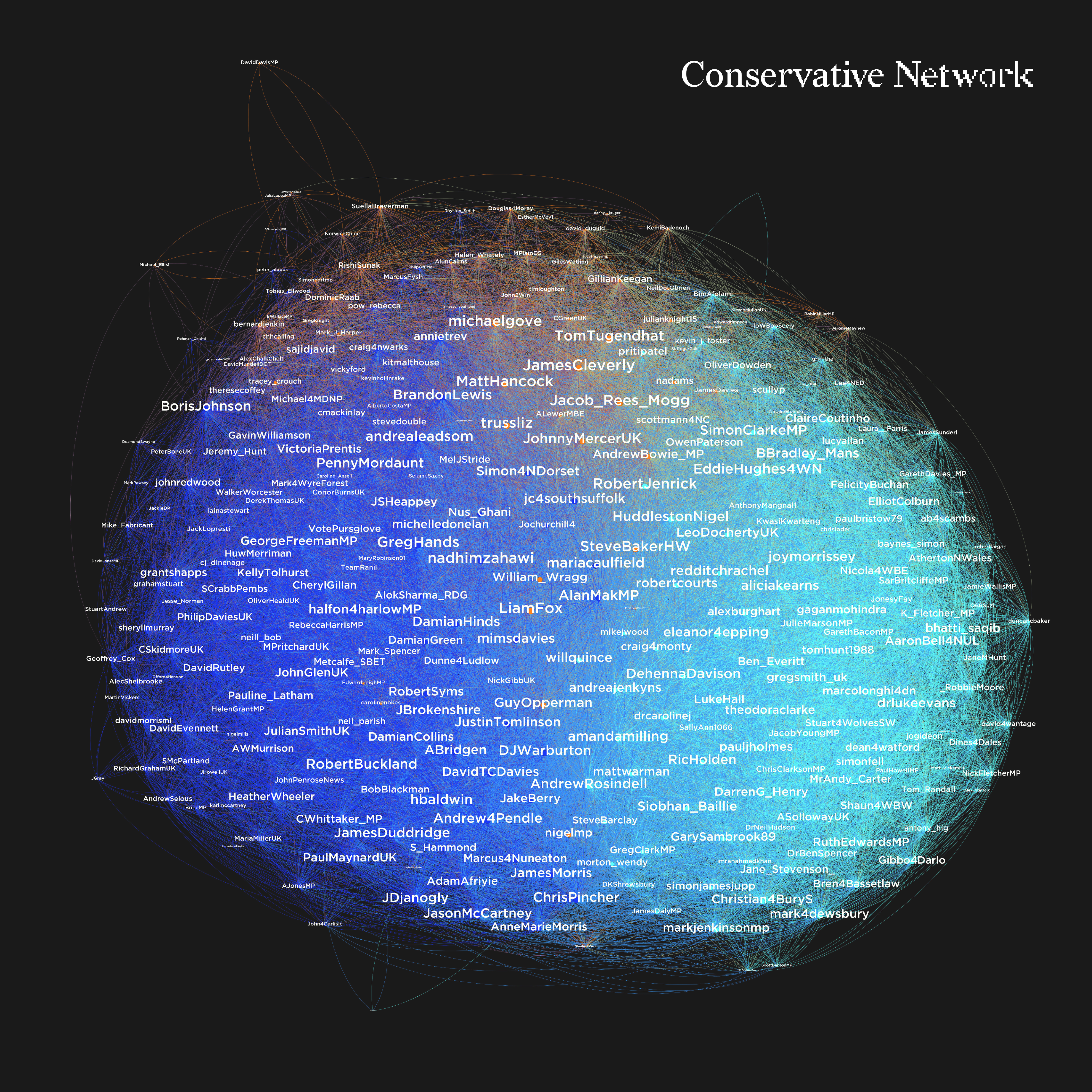

Moving onto the Conservative network, there are again three main modularity classes as shown in Figure 6 (although a few individual MPs actually had their own additional classes), (dark) blue, cyan and orange. The interactive version of Figure 6 is here: https://scottw2.github.io/UKMPsTwitter/ToryNetwork/. The division of this network is a bit more nuanced than that of Labour, as I believe what the groups reveal is only somewhat based on (left-right) politics and partly based on seniority or “who you know”.

Within the orange group appears to be many of the most prominent Brexiteers, e.g. Michael Gove, Jacob Rees Mogg, Tom Tugendhat, Dominic Raab. However, there are some orange group MPs who were originally backing Remain but ended up endorsing Brexit after the referendum e.g. Chloe Smith, Helen Whatley and Alun Cairns. So there seems to be some additional factors linking this group together.

The blue community is also quite diverse politically, and similarly to the orange group, features a few big Brexiteers like Andrea Leadsom and Boris Johnson. What is interesting to note is that Johnson appears, not in a central position in the network, but on the left hand fringe, with his allies mostly spread around the top left section of the network. A second factor held in common by both the blue and orange groups is the prevalence of most “one nation” conservatives in those two groups, compared to the cyan group. The blue group is particularly populated by one nation Tories, with senior one nation Tories like Damian Green (Chair of the One Nation Conservative caucus) and Robert Buckland (Vice President of the Tory Reform Group - a one nation promoting pressure group) part of this community, along with a large number of other MPs reportedly following this ideology. Members of the Cornerstone Group, a collection of Tory MPs who espouse “traditional” socially conservative values, are also generally located within the orange and blue communities. Additionally, MPs who were members of the Thatcherite Free Enterprise Group, founded by Liz Truss, are mostly situated in the blue community, but with some spillover to the orange and cyan groups - more so to the former.

The cyan community appears to be made up of some more senior MPs near the centre of the network, but also the majority of the new MPs who were elected for the first time in the 2019 general election, particularly in the fringe of the cyan network. This implies, to an extent, there is a possible division of seniority between the orange/blue and cyan communities. This may also explain why there are less members of the parliamentary groups mentioned in the previous paragraph within the cyan community - as new MPs may not have had time to integrate themselves into the different groups within the party, or at least haven’t been listed as members online yet.

Nevertheless, there still appears to be a division of seniority between the orange/blue and cyan groups, which could be down to a number of reasons. Firstly, as there is generally some clustering of the party based on a combination of seniority and ideology, maybe some of the old guard are somewhat suspicious of the new MPs, particularly those elected into traditionally Labour constituencies, and have thus kept their distance. On the other hand, this may just be a division within the Twitterverse, and newer and more senior MPs might just not have connected on Twitter yet. Plus it possibly may be to do with some kind of social media strategy during the general election, where new candidates’ Twitter accounts were set up and made to follow one another, so newer MPs are very interconnected with one another but have relatively fewer connections to many senior MPs.

Overall, I suspect the divisions of the network may be a product of all three reasons and maybe some others I haven’t thought of. This possibly reveals that current Tory MPs are a bit more cliquey and hierarchical compared to the Labour party (at-least on Twitter). Although this difference could also be due to the influx of new Tory MPs and decrease in Labour MPs in 2019. In any case, the current Labour networks appears to be more politically divided between the left and right compared to the Conservative network.

Figure 6: Conservative network of mutual followers - coloured by modularity class

Figure 6: Conservative network of mutual followers - coloured by modularity class

Conclusion & Final Thoughts

Overall then, as well as generating some quite nice graphs, considering the Twitter follower-following networks of UK MPs appears to give a number of insights:

There are of course some caveats that go along with this kind of analysis, as it firstly only captures a specific point in time. Secondly, MPs’ actions on Twitter may not be carried out by the actual MP, but by their team or by external agencies - so who they interact with and follow on the platform may not actually represent their own choices and viewpoints. There are also probably some differences in how Twitter is used by MPs with regard to how much time they (or their team) spend on the platform and what reason they are using it; for example, some may just use it for PR, others to interact with their constituents and the public, others may have mostly inactive accounts but re-tweet the party leader every once in a while.

In any case, I would be quite interested to extend this analysis to consider the follower-following relationships between MPs and verified non-MP users as I do already have the raw data for this. Looking at how these networks change over time could also be interesting. I would also think about further analysing the distribution of parliamentary groups within the Conservative network. Additionally, examining MPs’ tweets (e.g. the topics they tweet about, their sentiment and who they retweet and mention) is another project that could be intriguing.

References

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 3(1), 1. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/13937

De Meo, P., Ferrara, E., Fiumara, G., & Provetti, A. (2011). Generalized Louvain method for community detection in large networks. 11th International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISDA.2011.6121636.

Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S., & Bastian, M. (2014). ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software. PLoS ONE, 9(6), e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679

McLoughlin, L., Ward, S., Gibson, R., & Southern, R. (2020). A tale of three tribes: UK MPs, Twitter and the EU Referendum campaign1. Information Polity, 25(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.3233/ip-190140

Sleeman, C. (2015, April 24). The Twitter network for UK MPs. Nesta. https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/twitter-network-uk-mps/

Weaver, I. S., Williams, H., Cioroianu, I., Williams, M., Coan, T., & Banducci, S. (2018). Dynamic social media affiliations among UK politicians. Social Networks, 54, 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2018.01.008